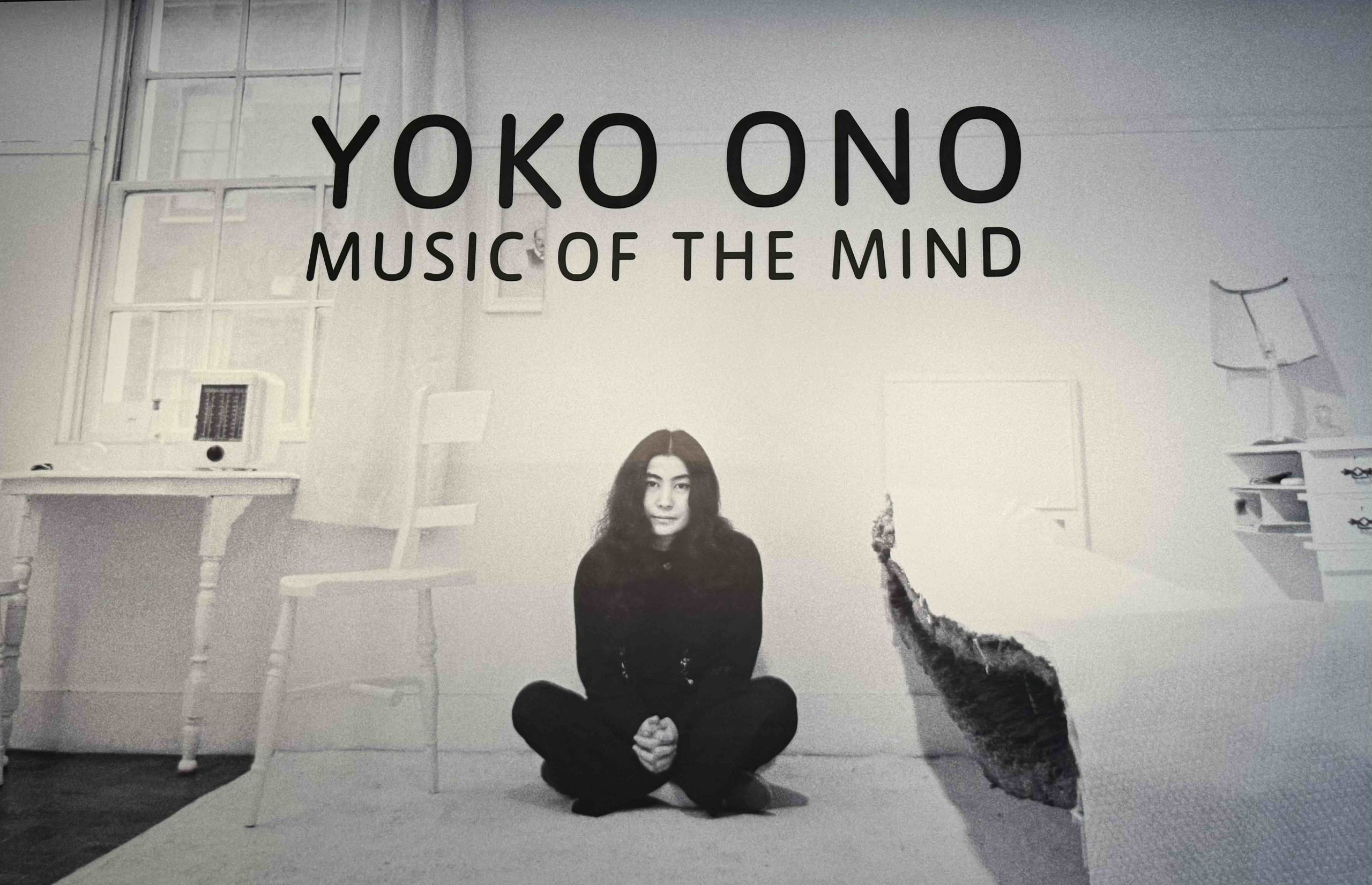

Give Peace Art a Chance

Words by Gemma Waldron

Hello. This is Yoko.

These are the disembodied words that greet us at the entrance to Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind.

As for minds, I go in with an open one despite the spectre of decades-long criticism threatening to sway my experience of Ono’s work. Luckily, any second-hand negativity is eclipsed by the sheer pleasure of moving through this Tate Modern exhibition in London on an otherwise uninspiring February afternoon.

Anyone hoping to separate art from the artist here has their work cut out. Death of the Author disciples need not apply. From the rotation of her serene speech patterns with guttural vocals, to a video close up of her unblinking left eye, and nonsense commands given in her signature no-nonsense way, Ono is present, and she’s inviting us to take ourselves less seriously.

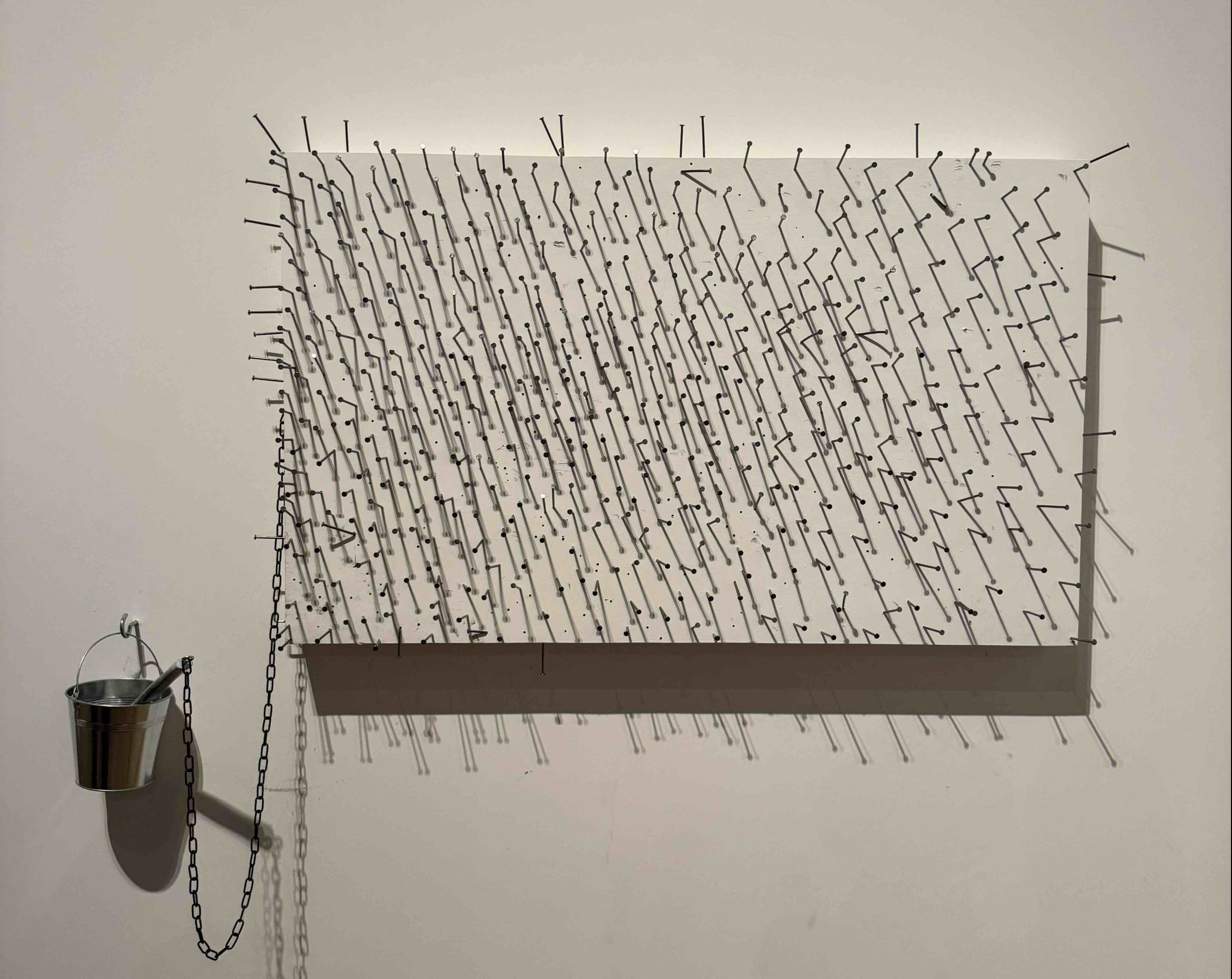

Playing along, I hammer a nail into canvas (‘Painting to Hammer a Nail’, 1961), pin an earnest, handwritten message to ‘My Mommy is Beautiful’ (2004), and obey some of the deceptively silly instructions from ‘Grapefruit’, Ono’s 1964 book, neatly typed and hung in individual clip frames. Little poems. I mentally stash ‘Sleeping Piece’ (1960) for later: ‘Write all the things you want to do. / Ask others to do them and sleep until they finish doing them. / Sleep as long as you can.’.

I stand at the huge TV screen and pay due diligence to the collective mooning of ‘Film No. 4’ (1966), a work described by Ono as ‘an aimless petition signed by people with their anuses’. I reflect on how a film which once caused such a scandal that Ono was forced to protest – with daffodils of course – outside the offices of the British Board of Film Censors, now seems quaint. My only other observation, as I spot a few goosebumps on those Bottoms, is that it must have been chilly in that filming location – the Mayfair home of art dealer Victor Musgrave.

Lumbered with a laptop bag and enough layers for London in February, I resist the invitation to clamber into a bag and make shapes (Bag Piece, 1964) as Ono and John Lennon once did to experiment with movement when race, gender, and celebrity are concealed. In truth, I’m much too shy. I don’t have the uninhibitedness of an artist like Yoko Ono. As if there is an artist like Yoko Ono.

When her work is not being written off to privilege or naivety, it’s Ono’s ego that comes under fire – such is the ‘confidence backlash’ often faced by successful women of colour. I’d argue that an artist who finds freedom by climbing inside a bag has a smaller ego than most. But Ono has form in being the unlikeable bogey woman. When John left The Beatles to pursue a solo career in 1969, it was she who took the heat from fans, the media, and his fellow band members (as recently as 2023, McCartney described Ono as ‘an interference’). Time to move on Paul?

Never mind the artistic differences, micromanagement, and money problems facing the Fab Four; easier to follow a well-trodden path of goodies, baddies, and femme fatales. After all, women – in life and in literature – have been scapegoats for men’s dodgy decisions since Eve dangled an apple before Adam, Helen of Troy somehow sparked the Trojan War, and Anne Boleyn got it in the neck for her not entirely unproblematic husband choosing to break ties with the Catholic Church.

Sitting to watch the video loop of ‘Cut Piece’ (1964), I’m struck by Ono’s fierce impassivity as her audience takes turns to cut away a portion of her suit. A souvenir. It surprises me to note the vulnerability I expected to see in the artist transferred onto the person holding the scissors. Ono burdens her spectators with performing until it is not she, the one being disrobed, who is revealed but them.

Unsettling as it is to watch participants grimly enthusiastic about undressing this silent, kneeling subject, it’s somehow worse watching those who apologise while doing so. Some take as little fabric as possible, but everyone queues up to take. Watching feels like being complicit in this public violation. Still, we’re thrown by the dual energies at play; Ono may never handle the scissors but they belong to her. rolex day date 36mm m128235 0038 mens rose gold tone jf rolex day date mens rolex calibre 2836 2813 m228398tbr 0004 automatic k&h auto breaking viewsapple galaxy a51 case https://www.ancientextractsshop.co.uk/product/ancient-extracts-organic-reishi-powder-60g-001171 https://www.canndidcbd.co.uk/product/canndid-20mg-cbd-pouches-blackcurrant-anise-buy-1-get-1-free-001442/ useful source

This calm management of the viewer’s experience characterises Music of the Mind. In Ono’s absence, her work is instructive, our movements choreographed. Or maybe I am leaning into that femme fatale trope. Because, coming back to The Death of the Author, Roland Barthes’s theory does apply here after all. The Fluxus tradition Ono’s work is born of undermines the role of the artist to make art, democratising the act of creating. At least that’s what they say. Could all be a ruse. But let’s lean in and imagine that Ono doesn’t create the art; we do, by looking at it.

I think my favourite, more unassuming exhibit might be ‘Morning Piece’ (1965). Ono is photographed on the roof of her West Village apartment, with people who’ve come to buy scraps of paper stuck to glass, each with a date and time to listen to the world come awake at sunrise. The flyer, audaciously – and yet sweetly – titled ‘mornings for sale’, advises ‘wash your ears before you come’. I don’t want to make sense of it. I just love it.

A glass pane with a bullet hole stands at the centre of the exhibition. ‘A Hole’ (2009) – an affecting piece implying the gunshot that killed Lennon at the hands of a man who cited Catcher in the Rye as his manifesto. I pause for thought at this horrible intertextuality. In the same quiet mood, I ‘Add Color’ (2019) to Ono’s Refugee Boat. The colour is blue. I read ‘ceasefire’ scribbled on all four walls and across the floor. Tiny voices. I add my own blue on white plea for peace.

With mind sufficiently nourished, so to music. Lester Bangs once wrote that Ono ‘couldn’t carry a tune in a briefcase’ and I’m inclined to agree. Ono’s purging, out of body grunts, screams, and wails are quite ‘yikes’ to those of us with ears spoilt by Beatles melodies. I doubt 91-year-old Ono could care less. Music of the Mind invites us to listen to her back catalogue, and it’s the least we can do while we’re here. I recommend people-watching in the gallery while plugged into noise cancelling headphones playing Ono’s 1973 album Feeling the Space. Try it.

The exhibition ends with Wish Tree (1996). The trees are positioned between entrance and exit, and I wonder if wishes change by degree of self-centredness depending on what point in the show we approach them. I’m unmoved by the wishes tied to branches, or by adding my own. This tradition-turned-art has become such a staple of festivals, weddings, and corporate events, that it feels as banal as Live, Laugh, Love etched onto driftwood and hung in a hallway. (Ono has her own version of this decor phenomenon, with the less platitudinal ‘PEAL, RUB, PEEL, TEAR, TAKE OFF’.)

Does engaging with ‘Wish Tree’ and ‘Add Color’ alert us to our power, or does it give us permission to scrawl an aspiration for peace and look away? Either way, Ono’s peace art has always relied on her commitment to love-as-a-solution and the domino effect of thought. It is beautifully simple. As she wrote in her 1983 letter to the New York Times, ‘Our purpose is not to exert power but to express our need for unity despite the seemingly unconquerable differences’.

As good-humoured, cheeky (yes, that piece and others), and irreverent as Yoko Ono’s work feels, it also carries a steely demand for peace. It is pretty cool walking through seven decades of ideas woven into new forms that allow the questions we ask of them to replenish. Leave the cynics to their column inches and visit this funny, clever, and emotional retrospective with an open mind.

Ready to Talk?

DO YOU HAVE A BIG IDEA WE CAN HELP WITH?